Anupam Roy, from Land of Resistance (2017)

IN TERMS of subjectivity and digital media, body augmentation, and surveillance, the lines between machine and human are increasingly blurred. The subject is bifurcated between a digital and analog being, each shaped in different but related ways by capitalism.

The cybernetic itself is neither a threat to subjectivity or inherently liberatory. The central problem is the coding of the cybernetic.

THIS IS the phantasmagorical being of the bourgeois cybernetic. What appears as “naturally” artificial is a literal encoding of social relations.

AS JODI Dean observes, the Internet is structured by “an ideology of publicity in the service of communicative capitalism.” Central here is the contradiction of participation. As Mike Watson argues, “we have to assume that the proliferation of online left content on major platforms such as YouTube and the streaming site Twitch is possible precisely because it is conducive to capitalism.”

In this way the use value of communication gives way to exchange value.

AS WALTER Benjamin argues, fascism “sees its salvation in granting expression to the masses – but on no account granting them rights...” While social media is not itself necessarily fascist, it is at its core expression without rights.

RICHARD BARBROOK and Andy Cameron situate the ideological origins of Silicon Valley at the intersection of Bay Area counterculture and the neoliberal turn; a fusion of “technological determinism and liberatrian individualism” among a highly skilled and contracted labor aristocracy.

Layers of this group came to believe they created cyberspace from individual genius, forgetting its origins in government subsidies and the DIY ethos of its earliest programmers. They embraced Jeffersonian ideals of petit-bourgeois “democracy,” eventually leading some to more overtly anti-democratic ideologies.

Barbrook and Cameron argue that Silicon Valley idealized a world of “Cyborg Masters and Robot Slaves,” in which human labor is minimized and power rests with the cybernetic labour aristocracy. Instead, there are, increasingly, cyborg-masters and cyborg-slaves. Barbrook and Cameron write:

At his estate at Monticello, Jefferson invented many clever gadgets for his house, such as a ‘dumb waiter’ to deliver food from the kitchen into the dining room. By mediating his contacts with his slaves through technology, this revolutionary individualist spared himself from facing the reality of his dependence upon the forced labour of his fellow human beings. In the late-twentieth century, technology is once again being used to reinforce the difference between the masters and the slaves.

This “democratic ideal” therefore, prefigures the “post-human,” hyper-Cartesian, and even dark Enlightenment ideas that would later percolate in Silicon Valley.

WHILE TECH neo-reactionaries are anti-populist they share with the proto-fascists hostility to the so-called “Cathedral” — a term initially used by cyber-utopians to describe the ideological apparatus of modernity (higher education, the press, the ideological arms of the state, etc.) — counterposing it to a supposedly open democratic bazaar.

The petit-bourgeois character of that bazaar — aided by a massive influx of finance capital — rapidly concentrated tech capital. It is no longer an anarchic market, but something more like a monetized counter-cathedral predisposed to erratic right-wing populisms.

The logic of bazaar vs. cathedral is playing out once again with a layer of tech speculators offering NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) as a way to overthrow the gatekeepers of the traditional art world (galleries, critics, curators, established collectors, art schools, art historians, etc.). But what they offer is a financialized instrument artificially making freely flowing digital images into rarefied commodities. All this is, again, backed up by finance capital, particularly through the large New York City auction houses.

We will be left with an art world that is just as rarefied and elitist — maybe more so — but without even the current pretense of the philosophical art-object.

The art fetish dies but the commodity fetish lives on.

AS JEN Schradie outlines in The Revolution That Wasn’t — her intensive study of right and left social media practice in North Carolina — conservatives have had much greater success online than civil rights and labor organizers.

Schradie argues that there are three interrelated reasons for this. One, social class. Two, organizational resources. Three, ideological difference. While most working-class people are now online in the US, access is inconsistent. Successful digital interventions and propaganda actually requires resources and organization. Labor and community organizations on the left were consistently outgunned in terms of digital propaganda by right-wing organizations.

In terms of ideology, left organizations often aim to activate and incorporate people into some kind of self-conscious activity. In contrast, Schradie found that right-wing organizations were largely focused on a sort of “good news proselytizing.”

THE DIGITAL code is determined by bourgeois ideology. As noted by Jessie Daniels and others this code is also racist. Ruha Benjamin calls this, referencing Michelle Alexander, the “New Jim Code.” In addition to “unintentional racism” there is a great deal of intentional racism as well, as with the N-Tech Lab’s Ethnicity Recognition Software.

THE NATURE of the present internet flows from the financial and productive functions of digital capitalism more generally. The Internet, contrary to its own mythologies, began as an “Internet of Things” – first scientific research and military operations, but soon after as a key tool in re-organizing global lean production.

Information technology became central in managing and reshaping the increasingly complex inputs and outputs of global finance, production and distribution. This is the material and economic “base” of the internet’s cultural “superstructure.”

AFTER MORE than a decade of quantitative easing by central banks — and the US Federal Reserve in particular — the investment class is flush with cash. But, as Michael Roberts notes, “the ‘real economy’ based on profitability and investment in productive assets stagnates.”

Speculative finance capital searches desperately — and stupidly — for places to hide and grow. What was once despairingly called “fictional capital” now invests in fictional/virtual worlds: in cryptocurrency, NFTs, and a hyperreal land-grab in the metaverse. In terms of the latter, some investors predict a “global market for goods and services in the metaverse” to soon reach “$1 trillion” (New York Times).

It is too soon to tell how much of this is pure speculation, how much is social madness, and how much reflects other aspirations of personified capital.

Even Roberts notes that there are “real world impulses at work in the cryptocurrency trend — the desire to eliminate financial intermediaries.” But the bourgeoisie as a class is still unwilling to give up its state-backed fiat currencies, using crypto as a substitute for gold, i.e. a place to sit on money because real world profit rates are too low.

Of course this is a disaster in numerous ways, including in its impact on the environment.

Bitcoin mining produces 35.95 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year, more than the country of New Zealand. NFTs alone produce more carbon than the country of Iceland. “A single NFT by one crypto artist,” Roberts writes, “consumed electricity equivalent to an EU citizen’s average energy consumption over 77 years.”

CAPITALISTS ARE abusing the amazing potential of the cybernetic in a myopic madness. But there is another possibility for the cybernetic.

As we wrote in Locust, what if, having become part machine, class-consciousness demands we figure out how to be in solidarity with that part of us that is machine? What if the machines, being dead labor, the products of previous generations of labor, are — in an animist sense — our working-class ancestors?

If the cybernetic blurs our subjectivity with dead labor, we wrote, it is inherently gothic.

OUR INABILITY to imagine solidarity with cybernetics is an extension of our failure to extend solidarity to our working-class siblings in general. The cybernetic flow could be different. We could enter and leave, at will, a consensual flow: infinite subjectivities in varied levels of self-determined contact.

IN AGGREGATE, digital communicative capitalism presents us with a totalizing capitalist metanarrative regardless of the discrete units placed into its flow. Digital social media has become a total installation, in which all aspects of IRL life are reframed, in which each unit finds itself in negotiation with a hidden bourgeois oversoul.

We counter with the gravedigger’s multiverse: infinite subjectivities in varied levels of self-determined contact.

ONLINE, WE perform how neoliberal capital sees the working-class, as an endlessly exchangeable multiplicity of supposedly “unique” (but always changing and reproducible) modules (of greater but most often lesser value). We do this in a space in which each person/subject/worker is seemingly lifted from social context.

In “Zombie Gallery? The German Ideology and the White Cube,” Danica Radoshevich argues that the white cube form is an expression of the bourgeois ideal. It isolates the “genius” art object and image beyond social context.

When we perform our digital selves we largely curate ourselves. In this way Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr and Twitter are the white cube writ large. But unlike the white cube, which also valorizes the unique art object by underlining its auric value, the digital space eradicates auric value. We imagine we will become more with every post and image (but the inverse is usually true).

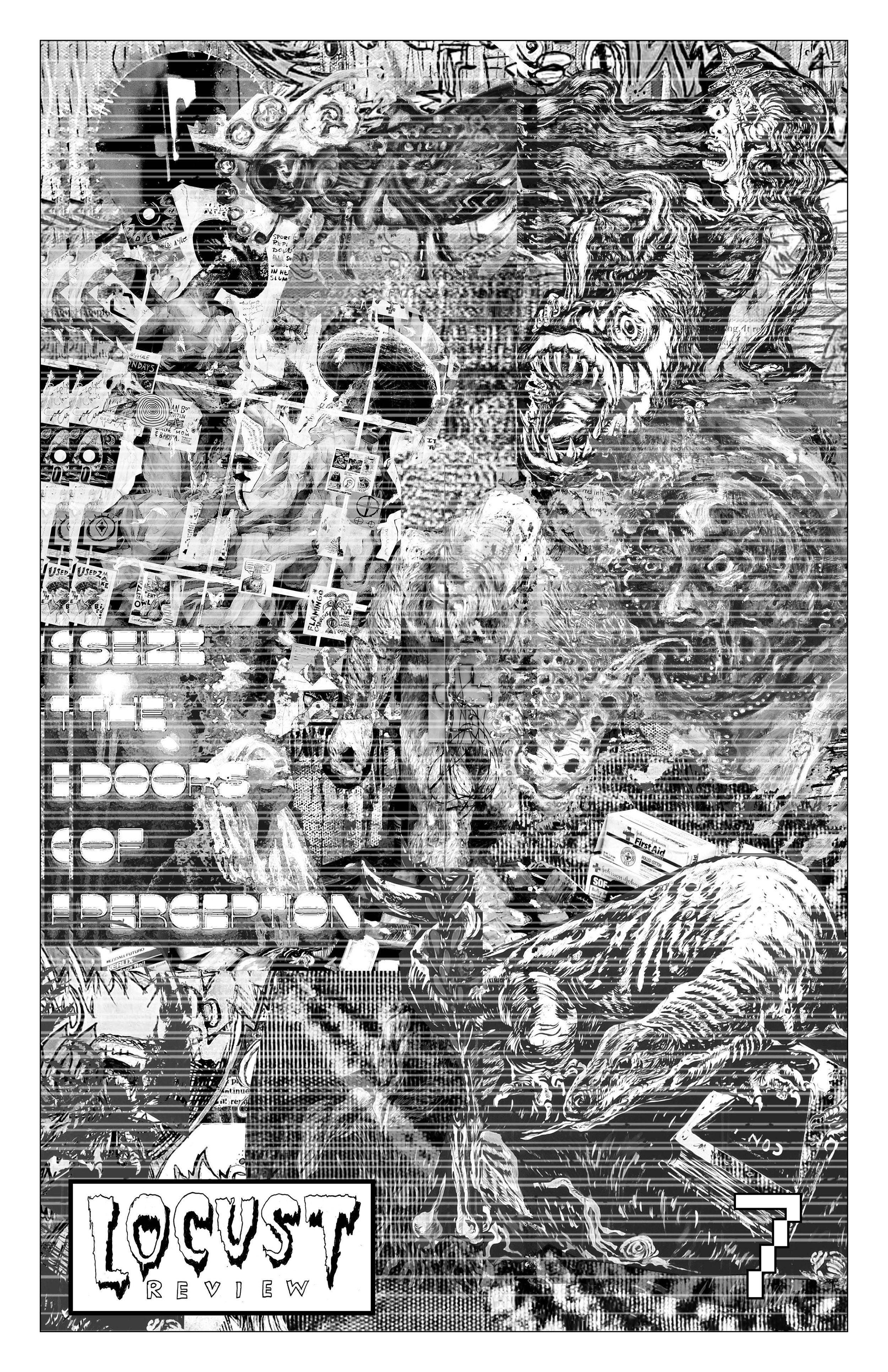

THE BIFURCATION of the cybernetic subject raises the need for a Brechtian Cybernetics: The use, exposure, alternation between digital and analog to help enable criticality and valorized self-expression in our cultural work.

As per Jodi Dean’s contradiction of participation, there can be no emancipatory politics without mass communication, yet communicative capitalism undermines emancipatory politics. The cybernetic has a contradictory relationship to a bifurcated subject. On the one hand easing identity formation — and pointing beyond the limits of capitalism but also threatening subjectivity and enforcing capitalist, racist, and heterosexist norms.

The internet promises democracy but delivers reactionary politics (and is designed to do so). It promises expression and valorization of the subject, but delivers, more often, dopamine denial and depression. Meanwhile the analog, at least in the arts, promises authenticity, but fails to deliver much more than rarefied bourgeois spaces, out of touch with the vast majority of the human race — as Amiri Baraka would say, “fingerprints of rich painters”... Or, empty art museum spectacles; Epcot Center immersion for the cosmopolitan bourgeois and petit-bourgeois.

This demands — in the arts — a digital and analog conflation. To weaponize each via glitch, switching between digital and analog/hand made, creating slow memes (Mike Watson) to interrupt the intentional irritations of the capitalist digital flow, eradicating aura here and recouping it there, coupling it all with IRL space and platforms for critical class reflection...

Subscribe to Locust Review for as little as $1 a month.

Submit work to Locust Review by e-mailing us at locust.review@gmail.com.